RED FIDDLE VITTLES

Forged by Pandemic, Strengthened by Hurricane

Matt Farr and Erica Beneke run Red Fiddle Vittles in Asheville, North Carolina. Though billed as “an Appalachian market and catering company,” Red Fiddle Vittles is so much more. Dedicated to their regional foodways, they source their ingredients from local farmers and provide steady support to their community—in good times and bad. Erica has more than twenty years of professional kitchen experience, including being crowned “Chopped" champion on the popular Food Network television program. Matt is from Memphis and brings a combination of event production, kitchen + FOH management, and community engagement experience. Partners in life as well as business, they answered some of Kitchen Table’s questions about mutual aid and the constant evolution of food businesses in an ever-changing world.

Erica and Matt

Matt and Erica met in September 2017 at a MANNA FoodBank event where Matt was working and Erica was volunteering. The following April they organized and catered a 250-person volunteer appreciation event for the food bank. In the process of organizing that event, they approached a downtown church about renting their kitchen space for a few days to prep. They sourced donations from local farms, Whole Foods, and Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. And had a chance encounter with Gladys Knight at the Food Lion in Fairview. The event was a huge success. It was a lot of work, but Matt and Erica knew that they were on to something big.

They picked up some private chef clients and started putting themselves out there as available for weddings and private chef experiences. Those couple days of renting the church kitchen turned into a few days a month, then a couple days a week, and then every weekend. It was a boot-strappy start for sure, lots of schlepping equipment and ingredients in and out every week. Catching deliveries when and where they could. They knew if Red Fiddle Vittles was to grow, then a shared-use kitchen was not the way.

Matt and Erica started a family and got married and began looking for a dedicated kitchen space in 2019—and then the pandemic dropped. They were exclusively a catering and private chef company at that point, in a shared-use kitchen with limited access, almost completely reliant on the tourism and event industries, both of which were all but shuttered for most of 2020.

The early weird months of quarantine are when the packaged frozen foods and take-home dinner concept first materialized. A new local grocery delivery service surged in popularity and Matt and Erica ginned up a take-and-bake cookie and biscuit program for this grocery to include in their online offerings. It was labor-intensive and definitely not profitable, but it gave Matt and Erica something to do.

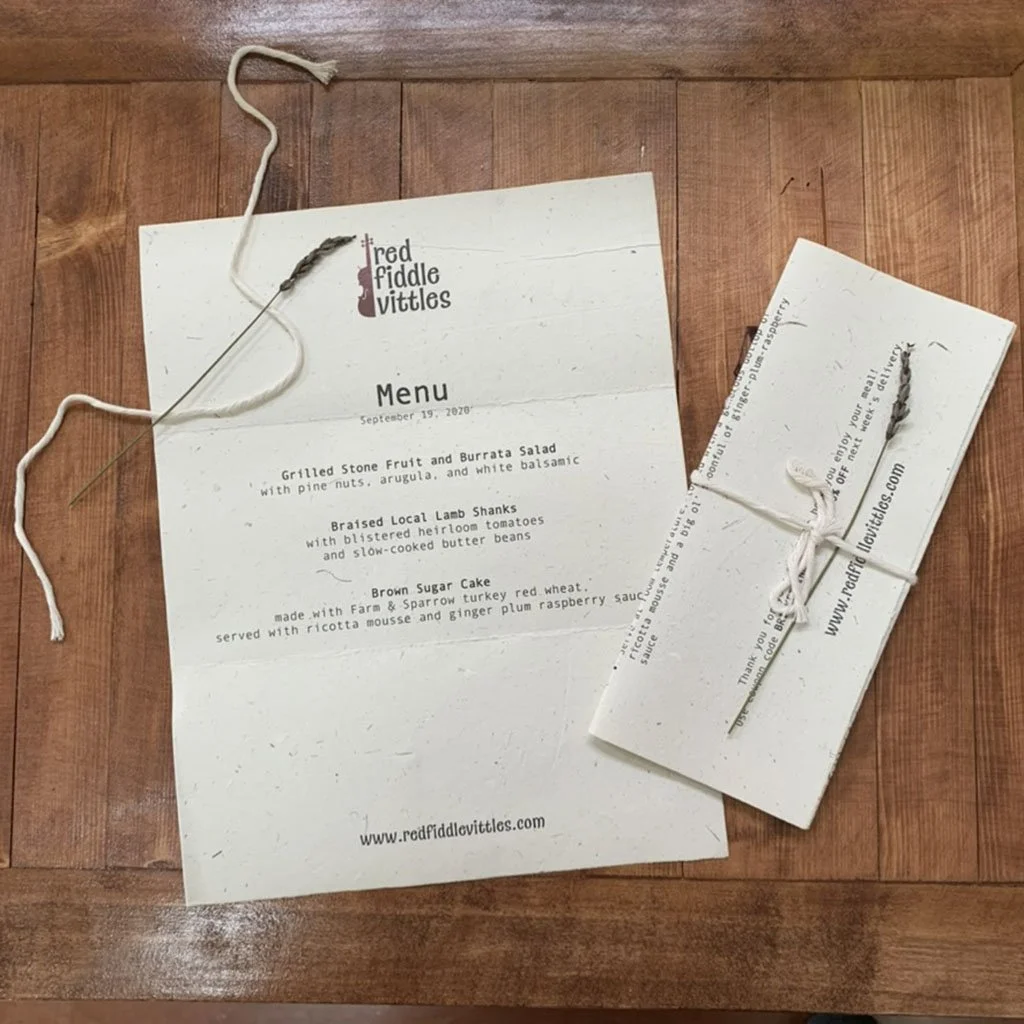

A couple months later they tried expanding their prepared foods program into what would eventually become their Take-Home Dinner, a composed, chef-prepared meal with courses packaged separately and reheating instructions included. The first iteration was delivery-based (still in the throes of pandemic protocols), and still being prepared on a limited schedule at a shared-use kitchen. It was a logistical nightmare. And also not profitable. Making a high-end meal with delivery (and inefficient kitchen overhead) affordable or even remotely marketable was challenging, especially then when this concept (at least in Asheville) was pretty new and unorthodox.

They tried to make it work, but orders didn’t take off and they exhausted themselves trying to make it happen (and care for a one-year-old at the same time). Fortunately, people started figuring out Covid testing, and smaller events and private dinners started booking again. People started travelling and Western North Carolina actually became a pretty popular spot for folks from larger cities to come get away from exposures or the quarantine routine. So business started picking back up, and Matt and Erica were really able to refine the private chef experience that Red Fiddle offers over those couple years.

Throughout 2019 and 2020 they had been working with a commercial real-estate agent, keeping an eye out for a commercial kitchen space, especially thinking that the pandemic could result in some permanent closures and vacancies. It didn’t. At least not quickly. Anywhere available with a big enough kitchen also had a big restaurant space attached to it; Red Fiddle didn’t need and couldn’t afford all the square footage. One day in spring 2021, Erica suggested that they have a look at an abandoned Little Caesars in a strip mall that they had driven by a thousand times, down the hill from a longtime client.

It didn’t fit what they thought they were looking for, but it fit the business that had evolved into something new during the time that they had been looking. It looked like any of the thousands of Little Caesars that exist out there. It had a little one-hundred-square-foot retail space, where they could sell their prepared freezer items and take-home dinners. The kitchen had good bones, having recently been updated before being abruptly abandoned. (The kitchen did need a little upfit, namely installation of a hood vent and some plumbing work. And getting that kind of work done during the supply-chain-and-labor issues in mid-2021 was a total trainwreck, literally the most stressful part of their small business journey.) The storefront is in a popular shopping center, with plenty of parking. And the location is at the heart of a busy and well-established commercial corridor with tens of thousands of drive-bys a day. It was the perfect place they never knew they needed for getting their quirky little business off the ground.

Overall, the current business model emerged as a result of uncertain times and a pivot toward something that struck a balance with their lives as new parents; offered multiple revenue streams for when disaster strikes (which it did again in 2024 with Hurricane Helene); and served as a resource and asset to the community. Red Fiddle Vittles is a more resilient business because of the challenges they’ve overcome, the creativity that those challenges sparked, and the community investments that have always been at the heart of everything Red Fiddle Vittles does.

THE INTERVIEW

KITCHEN TABLE MAGAZINE (KTM): How do folks who’ve spent decades in the already fragile industry of food service pivot, and continue to grow and make food, AND pay the bills as we encounter extreme weather events, struggling economies, and a fractured social fabric?

MATT: We’re figuring it out as we go. There is a strategy, and it’s to be adaptable. Prepare for anything. Have a plan. Throw it away sometimes. The best thing we ever did was to embrace the uncertainty; to develop multiple pathways to survival. To give ourselves as many options as possible in a constantly changing world. From local weather events to mandated pandemic shutdowns to global supply chain issues, our profit centers and forecasts have shifted in major ways every couple years as we sought ways to stay in business. At each turn we’ve refined various food programs, as the conditions have dictated which program is the most practical and profitable to hone: retail storefront, weekly take-home dinners, private chef experiences, large event catering, pick-up/drop-off platter catering, delivery service. At this point, we offer all of these services, but we have added them one-by-one over time based on market conditions and how our evolving vision best serves our community and our customers.

What various roles have you each had in the food & beverage space?

ERICA: I knew I wanted to be a chef when I was twelve and have never looked back. My first paying job was in Trumansburg, New York, at a small catering company. I would come in after the catering crews would leave for an event and clean up the kitchen. It wasn’t a glamorous beginning, but it gave me a glimpse into a career and a community of talented and unique humans that I could call my people.

I started as a server’s assistant at Taughannock Farms Inn at fifteen and eventually moved into the kitchen, starting in the dishpit before moving to salads and desserts. I worked there through high school and came back to work during breaks from college. I was promoted to sous chef after deciding to take a break from college.

After graduating with a culinary degree from Paul Smith’s College in the Adirondacks, I headed down to Austin, Texas to immerse myself in an exciting and growing food scene. While I got myself settled, I picked up event staff banquet server gigs, cocktail waitressed at University of Texas football games, checked tickets at Austin City Limits Music Fest, and got paid to be an extra on Friday Night Lights. You know, Texas things. I eventually landed a job as a line cook at Max’s Wine Dive in the heart of downtown Austin. It was a new and quickly growing restaurant. I worked every station in that kitchen, quickly working my way up to executive chef by age twenty-four.

A little after that, the whole Chopped experience happened. It was an exciting opportunity, but one that didn’t come without some strings attached. The more executive responsibilities I was expected to handle, on top of greeting anyone who walked in and wanted to meet the Chopped champion, the less I was able to do what I love. It was too much. I needed a break. I meticulously set up the kitchen so I could take a real vacation after over five years of eighty-hour work weeks. During that week-long vacation, corporate hounded me about work constantly and I realized that I had to get out and find another way. I moved to Asheville to be closer to family (my sister lives in Charlotte, and my dad had just moved to Asheville), and to explore Asheville’s popular food scene. I knew that working with food was my calling, but needed to find a way to do it that was more sustainable. I was doing in-home private chef work when I met Matt and we just kind of started working in the kitchen together and spinning up business ideas for how we could leverage our skills to build something together.

MATT: Erica is the real creative and executive powerhouse in the kitchen. My role at Red Fiddle is more that of a general manager. I handle sales, marketing, HR, and finance. I also jump in on prep or dishes or service whenever there’s a need or a gap.

My background is primarily in nonprofit programming and development, having served as an environmental educator for a local park conservancy in Memphis, a major gifts officer for The Nature Conservancy in Nashville, executive director for Bike Walk Tennessee in Chattanooga, and finally volunteer manager for MANNA FoodBank in Asheville. In all of these positions, I was managing or serving a role in events almost constantly, from intimate and highly orchestrated donor dinners to community-wide festivals drawing thousands. At various points and often throughout my nonprofit career I was managing budgets, organizing people, drafting proposals, creating marketing pitches, and building community. The breadth of skills I learned in the nonprofit world is vast, and I feel like I deploy almost all of them daily in what I do at Red Fiddle.

I’ve also had an interest in growing and making (and eating) food from a young age. My granddaddy had a farm that was always a thrill to visit, and I grew up in a pretty rural area outside Memphis where we had gardens and grew food. I spent a lot of time preparing very Southern recipes with my very Southern mother and grandmother (not grandma or granny or gramps or gam-gam…grandmother. Excuse me: Grandmother. She would prefer it capitalized). I went to college at the University of the South and worked at a small pizza and sandwich shop on campus all four years I was there. I started as a prep cook making sandwiches most afternoons and slinging pizza dough most nights, and eventually worked my way up to managing the place by my senior year. In the summers, I worked a few server gigs at some nicer restaurants back home in Memphis.

It took about a decade to fully come back to food, and started with building a community garden program in Memphis from 2010 to 2014, creating a space where kids from food deserts could grow things. After a divorce, and in an effort to realign some life stuff, I signed on to work as the Outpost Cook for the Nantahala Outdoor Center’s French Broad River Outpost in Hot Springs, North Carolina, cooking daily breakfasts and dinners for twenty to thirty raft guides for the summer of 2016. When that season concluded, I stayed in food and worked at the food bank in Asheville from 2016 until 2019. Erica and I met in 2017, started Red Fiddle in September of 2018, I quit my job at the foodbank on January 1, 2019 and the rest is a history that we’re still writing.

I didn’t think food service would be a career path when I was working in the industry during college; my academic brain had whimsical fantasies of lofty pursuits for wisdom and righteousness and a life in the kitchen didn’t seem to fit within those sophomoric visions. Little did I know that kitchen life would hold the key to a future that included starting a business and a family and a life in Asheville…some of the wisest and most righteous choices I’ve ever made.

Who are some of the local farms you work with? Have you teamed with any farmers on a particular crop you like to work with?

MATT: Some of our favorite local farms (foragers and fisheries) that share our values and consistently provide exceptional food products include Sunburst Trout Farm (Waynesville, NC), Dr. King’s Carolina Bison (Leicester, NC), Hickory Nut Gap Farm (Fairview, NC), Wild Goods (Ashville, NC), Tiny Bridge Farm (Hendersonville, NC), and R Farm (Weaverville, NC).

We’ve partnered directly with most of these producers for one thing or another. We’ve worked with Sunburst to get the right trout roe for a super fun deviled egg we did for a local food festival a few years ago. We worked with Carolina Bison on a special 2”x 3” English-style custom cut on their bison short ribs, which we feature alongside Sunburst Trout fillets in a super local menu we call “Appalachian Surf and Turf.” We also sell red-wine-braised bison short ribs from our freezer case in our storefront, as well as a house-prepared smoked trout mousse that features a hickory-smoked trout from Sunburst. We have a lot of fun finding ways to weave our favorite local products across various food programs.

If we’re ever looking for something new or different from what the farmers we work with are able to offer, we often turn to the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP). They are a hub and connector for local food and a key resource for our local food economy. Red Fiddle Vittles supports ASAP philanthropically in many ways throughout the year.

The whole of Western North Carolina (WNC) was beat up and ravaged; are there still lingering issues with sourcing and supply chains? How has the food community responded?

MATT: This is a big question, and my answer will be insufficient. I’ll share something a raft guide friend and firefighter with the Kingsport Fire Department said in the weeks following the storm:

“I was a part of a SAR mission down the Nolichucky gorge yesterday and it is not the river we all know and love. The deck has been completely reshuffled and the hand we’ve been dealt has some major wild cards in it.”

I feel like Helene’s impacts to our local food system mirror these words about the river. The “deck has been reshuffled” in Asheville and WNC’s food system for sure. So many food businesses closed following the storm. Many never reopened. Many others tried and had to close a few months later. Some new ones are opening up.

As for our personal experience with sourcing and supply chain, two key local product distributors lost their warehouses to flooding. One has since come back, but we’ve had to source directly from dozens more producers than we did before the storm. The other never re-opened. As a testament to the resiliency of our local producers and food system, we can’t think of too many farmers or food producers that aren’t back in business in some capacity. The footprint of WNC’s food system is definitely smaller due to Helene, and time will tell if it’s able to bounce back. We suspect that it will, but maybe with fewer conventional restaurants and more alternative food concepts and markets like ours.

How is the take-home dinner business doing? Are there any new trends you’re noticing in this space?

MATT: It’s grown steadily since we opened the shop in February 2022. There’s been a learning curve. Our concept was pretty new for Asheville. It certainly hadn’t been done at the level we do it. Consequently, people had to try the food to understand why we charge prices similar to good restaurants. Once folks figured out the program, how good the food is, and how it works, they often quickly become regulars.

There are a lot of people out there who don’t like to cook but do like to eat good food. We have tons of older customers who simply don’t want to cook anymore after decades of feeding huge families. Tragically, we also have a number of older customers whose often recently deceased spouses were foodies and chefs and made all the food. Now these people come to us to fill those spaces in their lives. It’s a pretty special role and relationship that we cherish.

We anticipate that as large parts of the population ages and Asheville’s reputation as a major retirement destination remains strong, our market will only grow. Our little shop is less than a mile from many of the area’s nicest fifty-five-and-older communities. As far as making a restaurant or food business work these days and into the future, the keys to success have as much to do with the food concept and quality as it does the location, convenience, and relevance to a target market. This isn’t a new strategy, it just needs to be applied against shifts in the ways and places people are living.

Our pivot since Covid has also been one in which we’ve sought to diversify revenue streams in order to give us options when natural disasters, supply shortages, or economic downturns happen. As devastating as Helene was, our ability to keep our farmers paid and our staff employed throughout was a true proof of concept. While we’re constantly refining things and seeking efficiencies, we now feel like we are operating a resilient business model, forged by a pandemic and strengthened by a hurricane. We also feel like we’re able to lead a balanced, family-centered life. We eat dinner as a family almost every night, and usually have availability on the weekends to schedule and enjoy meaningful family time. In uncertain times, we are certain that we’re doing the right thing and building a family equipped to adapt and respond to a changing world.

How do you promote Red Fiddle Vittles? You’d mentioned the loss of tourism since the hurricane, are you doubling down on the local community?

MATT: We will always double down on the local community. Our most sustainable promotion strategy is built into our business model: many of our best retail customers first tried our food at an event we catered, and we book many catering gigs through people learning about our retail shop. Just getting our food in people’s mouths is the most effective promotion strategy.

Having a storefront brick-and-mortar with a big sign on a busy road is also helpful. Expensive, but helpful. So many catering outfits operate out of shared-use or not-super-inviting industrial areas or commercial kitchen spaces. Having ample parking, regular hours, and a variety of food options for people to purchase and try sets us apart from the way many catering companies do it. These little differences are major draws for locals who want to connect with food people and be a little closer to the food they eat.

Our weekly newsletter is our most effective marketing tool. It goes out every Sunday to about 2,500 people and includes the upcoming week’s take-home dinner menu and freezer item updates, as well as little blurbs, vignettes, ruminations, and interviews about local food. People really value the time and intention we put into our newsletter, many of whom look forward to it every Sunday as a weekly meditation on local food. It makes people feel good about the good decisions they’re making for their health, for the environment, and for their community by choosing to support local food businesses. We’ve seen people move from being local food-curious to being completely invested local food advocates, donors, and volunteers through the connections that they make in our shop and with the information we collect and share about our local food system. It took over four years to build our email list and it felt silly when it was just going out to like forty people, but we just kept plugging away at collecting customer emails and here we are driving major revenue with a weekly email.

Tourism is and probably always will be a very important part of how Asheville works. It is certainly a major part of making our business successful, as destination weddings and tour groups comprise a big part of our catering revenues. We very intentionally chose to diversify our business model to hedge against the inevitable fluctuations in tourism numbers, which have been historically volatile over the past five years. If tourism dropped to zero tomorrow, our business would suffer and we’d have to make some very hard decisions, but we’d survive.

Obviously, there doesn’t seem to be a path forward to going back to the old ways. Restaurant culture in Portland is figuring out how to both fill seats AND pay staff living wages, offer benefits, etc. What would you like to see food service develop in the coming 5-10 years? Will restaurants as we know them still be viable? (Not that they ever were.)

MATT: People will always keep trying to make restaurants work. There are some deep-seated human urges to create things for people to enjoy, and to enjoy things that people create. Going out to a restaurant already is a luxury for many people. We expect that will be the case even more so in the future. Due to the way our globally commercialized and subsidized food system works, there is a vast misunderstanding of the true cost of the food we consume as a society.

Alternative food concepts, ones that give people the flexibility to enjoy good food outside the four walls of a restaurant are popping up all over the place. Over the past three years, new local markets with some similarities to ours have opened in downtown Asheville, West Asheville, Black Mountain, Canton, and Hendersonville. The food truck scene feels somewhat stalled, but there are definitely some favorites around town that get cult followings in the way popular restaurants used to. A variety of home-based bakeries and a couple other prepared foods companies appear to be successful as weekly vendors at WNC’s robust farmers market network (which is also heavily coordinated and promoted by ASAP).

Maybe we’d call it a general loosening and diversification of the food scene. It was already well underway before Helene, but the storm’s effects certainly fast-tracked some difficult decisions for a lot of people in Asheville’s food community. The rigid confines and rising costs of operating a restaurant on the old model is hard to square with what people are willing or able to pay for food. If you get the formula just right…location, foot traffic, timing…and you’re exceptionally talented not just at being a chef, but also at marketing, human resources, and finance…and you always run things absolutely perfectly so an unhinged customer or employee doesn’t troll you online…maybe you’ll have a chance at running a break-even restaurant.

It’s a stifling and suffocating realization for any chef aspiring to open a restaurant. One thing we’re seeing is lots of longtime industry veterans coalesce into new restaurant ownership groups as various flagship restaurants in Asheville have closed. We’ve seen as many–probably more–of these fall apart (sometimes disastrously) as we’ve seen succeed, but the ones that do end up working seem to be pretty resilient and responsive businesses.

As far as business and government’s role in facilitating a shift in the traditional model and chronic undervaluing of industry workers, there could be tax incentives, sales tax rebates, or even grants for businesses that pay a certified living wage. And not just token incentives—big-time breaks that make running a business easier and more lucrative. Put money in the hands of the people doing the work. Keep money in the business that’s offering the work. It’s pretty straightforward to us. But breaking one insolvent industry model using the tools of an insolvent and imperiled democracy feels slow and egregiously daunting at best, and like a complete waste of time at worst.

We think that the best way to create systemic shift is to inspire and amplify new perspectives at the grassroots level. True leaders who make differences at high levels emerge from the people and communities they once were inspired to support and sustain. Over time, the more people who feel inspired to create change, the more likely change is to occur. It’s also slow work, but it somehow doesn’t feel daunting. It feels achievable. It feels inspiring in itself. Do one thing that could inspire someone today. Big or small. Directly or indirectly. That’s it. If everybody lived by that rule, what kind of world would we be living in? A pretty dang good one, I think.

And that’s central to our approach in running the kind of food business we do. We haven’t cracked any magic codes, but we are trying to use our business for more than just making money no matter what. Both in terms of personal fulfillment and purpose, but also as a way to create change and do things that inspire people to think about making food choices that benefit themselves and their community.

What other ways have you been involved in community-building more recently?

MATT: In the wake of Helene and more recent cuts to Medicaid and SNAP, we launched Pass the Plate, a pay-it-forward initiative that solicits donations to put chef-prepared, locally-sourced meals into the hands and households of those facing food insecurity. Since October 2024, we have raised more than $75,000 and served more than 10,000 free meals.

On September 27, 2025 we are participating in the Utopian Seed Project (USP) Trial-to-Table Dinner Series. USP does some really important work, specifically identifying and promoting seed and produce varieties that are resilient to extreme changes in the climate. For this dinner series, USP recruits a group of chefs and gives them a featured ingredient to prepare dishes with to share at these ticketed dinners. For this dinner we’ll be preparing two savory dishes featuring Southern Crop Peas.

Every February, we donate a breakfast for 250 farmers and food producers attending ASAP’s Business of Farming Conference. We also are a lead sponsor for ASAP’s Farm Tour, which takes place every September.

How do consumers play a part in the fragile dance that is the food scene?

MATT: It’s a fragile dance, indeed.

The work involves overcoming the systemic misconceptions about what it costs to produce good food. There has to be a shift in how society values food and the people who make it. We’re talking about realigning how a society understands and values something that everyone has a (usually strong and often misinformed) opinion about. It’s big work. The best thing any consumer can do is to get closer to your food in some way. Big or small. You don’t have to visit a farm or have lots of money to learn more about where your food comes from. Try to understand how many people had a role in getting that food to your plate. Maybe you won’t like the answer you find, and that’s ok. Maybe it will motivate you to get creative about finding something that makes you feel good about what you are eating, something that makes you want to celebrate yourself and the role you and your food choices play in your community.

What is your favorite pizza/pizzeria?

MATT: Pizza Night on Fridays is an unshakable, non-negotiable family tradition. We can be found at White Labs Brewing Co. in Asheville most Friday nights, either picking up to bring home for a movie night or enjoying as a family in their taproom (our brother-in-law is also the chef there so it’s always a treat to eat there when Uncle Nick’s slinging the ’za). White Labs is primarily a yeast producer for the beer industry with one location in San Diego and one in Asheville. They launched a taproom and brewery program in 2017 that features ferment-forward menu items and a fantastic sourdough, wood-fired crust that’s consistently the best we’ve found around here. We went on some of our very first dates there back in 2018 and are still going back every week, now with two kids.

In ten years, where and where will you shop for/grow your food, and what’s for dinner?

MATT: Asheville has an incredible variety of farmers markets, often called “tailgate markets” around here. We see ourselves continuing to shop at Asheville’s tailgate markets. It’s the best way to ensure farmers are maximizing their revenues. It’s a community of good people that we enjoy. And the quality and variety of food products and ingredients is unparalleled. We don’t see ourselves doing too much else different in ten years than we are doing now.

With any luck, in ten years we’ll be eating something similar for dinner to what’s on our take-home dinner menu this week:

Roasted Peruvian-Style Half Chickens with Spicy Green Sauce

featuring chicken from Wild East Farm (Marion, NC) and peppers from Gaining Ground Farm (Leicester, NC)

Quinoa and Grilled Corn Stuffed Cubanelle Peppers with Smoky Tomato Sauce

featuring peppers from R Farms (Weaverville, NC), corn from Mountain Food Products (Asheville, NC), and tomatoes from R Farm (Weaverville, NC)

Hominy and Summer Vegetable Stew with Squash, Blue Potatoes, Canary Beans, Aji Amarillo, and House-made Queso Fresco

featuring squash from R Farm (Weaverville, NC), blue potatoes from Sleight Family Farm (Pleasant Gardens, NC), and dairy from Homeland Creamery (Julian, NC)

Melon, Tomato, and Cucumber Salad with Lime, Mint & Basil

featuring melons from Mountain Foods Products (Asheville, NC), cucumbers and herbs from Gaining Ground Farm (Leicester, NC), and tomatoes from R Farm (Weaverville, NC)

Arroz con Leche with Candied Tomatoes & Marigold

featuring tomatoes from R Farm (Weaverville, NC), dairy from Homeland Creamery (Julian, NC) and rice from Tidewater Grain Co. (Oriental, NC)